Apparently, how many and how long lactating mothers breastfeed have virtually no influence on the diversity of the milk microbiota – contrary to popular belief.

A recent study explored the associations between breastfeeding characteristics and human milk bacteria, the journal Scientific Reports reported.

Introduction

In addition to providing essential nutrients, breast milk plays a crucial role in the development of a healthy infant’s gut microbiota. The bacteria in breast milk promote the growth of beneficial bacteria and prevent infections from colonizing the stomach.

For the first six months of life, the majority of health organizations advise that infants be exclusively breastfed. Microbes like Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Acinetobacter, and Cutibacterium that are normally found in the mouth or skin are present in human milk. These are most likely from the baby’s mouth and the mother’s skin.

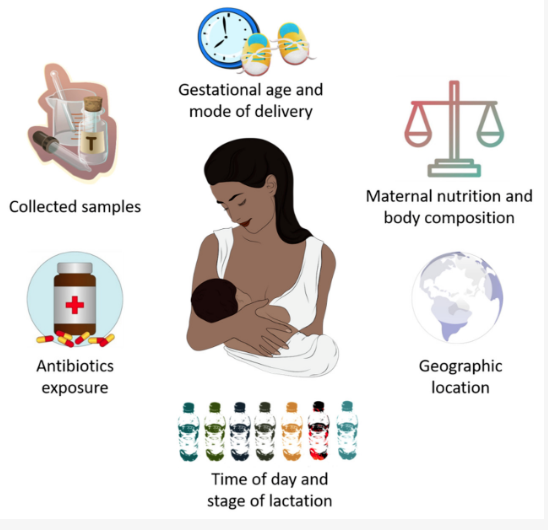

The amount of milk produced by nursing women varies greatly, as does the frequency and length of their daily breastfeeding sessions. Would this have an impact on the bacterial makeup of human milk?

Results of the study

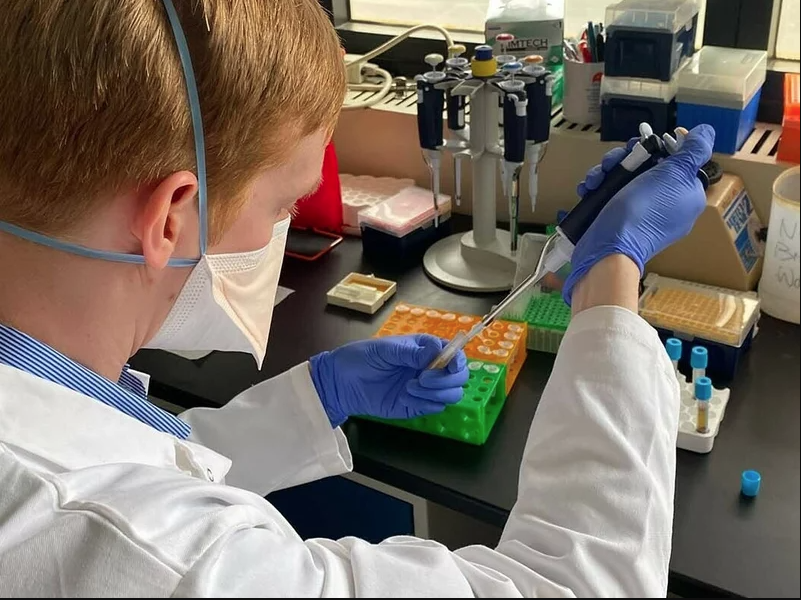

the study was based on breast milk samples collected from women in the Birth Cohort of the Breastfeeding Longitudinal Observational Study of women and Kids (BLOSOM).

Importantly, the milk samples were only from one breast for each participant and not both (and most moms were feeding their babies three months after giving birth).

It might also not be as generalizable in other populations, because the sample was mostly (if not totally) Caucasian mother who had given birth to a number of children.

More than 30, 000 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) from hundreds of bacterial species were found in the samples and almost 90% of the bacterial sequences in the samples were classified as belonging to taxa that represented 0. 5% or more of the total.

Microorganisms which appeared in the milk were similar to those present in the skin and oral cavity. The dominant species were Cutibacterium acnes, Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus salivarius. Since the percentages varied from person to person, they contributed 15. 6%, 13% and 12% of the sample, respectively.

The proportion of S. salivarius ( %) in the sample but not the proportion of other taxa, had a slight correlation with the breastfeeding duration (because some backflow into the breast ducts is thought to occur during sucking). Therefore the presence of S. salivarius in the mouths of healthy newborn babies may have some correlation with the breastfeeding duration. Properties of human milk microbiota were not related to any other species.

The structure of the microbiome was fairly similar in all samples, which suggests that other factors than length, frequency or amount of breastfeeding do not affect the microbial makeup of human milk.

Some scientists say the microorganisms pass from the baby’s mouth to the breast glands, and a study in Guatemala suggest this: milk samples from moms who exclusively breastfed had higher levels of many Streptococcus and other species in the oral cavity than milk samples from moms who took in supplemental feeds.

Very interesting point here, because the species are present in pre – colostrum prior to breastfeeding. It is possible that these bacteria colonize the breast and become more common once breastfeeding begins.

Obviously the time spent at the breast every day increased with frequency of breastfeeding. Thus the microbiome of the milk may be more affected by the total amount of time in which the newborn is exposed to the oral bacteria in the breast than the number of feeds.

The interesting part is that no change in the microbiota was found to be related to length of nursing, this may have been because relative abundance was used instead of absolute numbers (some bacteria may grow so much when repeated exposures occur that they can hide relationships with species with lower relative abundances).

Nothing about the amount of milk removed increased over a longer 24-hour period.

Significant advancements in techniques like quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) may be able to shed light on these issues. Future experiments should be carried out with a wider sample (with a wider range of socioeconomic background and ethnicity). Such experiments should begin after three months before delivery.

Additional elements that might change the microbiota in breast milk

Conclusion

Differences in nursing practices only slightly changed one breastmilk microbial characteristic. This implies that “the milk microbiota is generally unaffected by variation in nursing methods.”

Future studies with more varied individuals and sampling from both breasts are necessary since the results could not apply to other populations.